We were sitting on the porch, admiring my beautiful irises, when I suddenly realized I should be saving the dark-hued blooms for natural dyeing.

I'm hosting a natural dyeing online workshop this summer to teach the adoptive moms of my grands how to dye with avocado pits and red onion skins. They've done family tie-dyeing with conventional dyes and thought it might be fun to learn to dye with plants and table scraps.

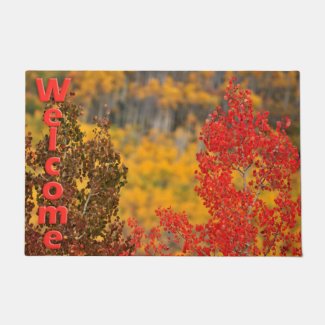

I looked at my Men in Black irises, which are just the most beautiful shade of deep, dark maroon. Surely they would dye just like "black" hollyhocks, right? (Which also are beginning to form blooms.)

My purple irises are pretty, too, and I wondered what color they might make.

So I ran inside and did a quick internet search. Iris petals make green dye, but it's fleeting. It's fugitive. It doesn't last.

I'm not cutting my lovely flowers for temporary dye. I'd rather try to match the colors of the flowers with conventional dyes that last.

When I rejoined Lizard on the porch, I saw the towers of lupine and wondered if they might make a lasting dye. I'd recently read about several natural dye experiments featuring lupinus, and how it's actually considered an obnoxious weed in Alaska. I thought if we ever do get to live out our dream of two years in each of the places we'd like to live and photograph, people in Alaska are not going to like me very much because I. Love. Lupine. !!! I ran back inside and did another quick internet search.

Lupine is fleeting and fugitive. It can make some pretty turquoise. Which doesn't last any longer than the actual flowers. I really love my lupine, and I'm not chopping it down to dye two-day colors. I'd rather try to match the flower colors and the fleeting colors other dyers have achieved, but with conventional dyes. I love mixing colors and experimenting. I especially love that the colors from conventional dyes last. As long as you follow the instructions...

I joined Lizard on the porch one more time and realized I have been thinning out my prolific salvia every weekend for three weeks now. I will have to continue thinning out the plants throughout the summer, unless I want a jungle of salvia. I like it, but not enough to let it choke out everything else in the garden. Perhaps salvia is a good natural dye...

Back inside the house I ran, and click, click, click... away my fingers took to the keyboard once more. Salvia actually is a member of the sage family. No wonder it smells so nice when I cut it down! Sage as a natural dye can last a bit longer, but it's going to be yellow. Not lime green. Not purple. Not pink. Not turquoise. I can dye a range of yellows with conventional dyes. It doesn't take as long as natural dyeing, and it doesn't have the three-month stench of plants fermenting in the sunlight all summer long. So I will keep thinning the salvia, enjoying the fresh scent and making porch and kitchen bouquets that last a good couple of weeks or more, plus, keep the seeds from spreading all over the neighborhood.

The hummingbirds, hummingbird moths, bees and butterflies probably won't be too happy, but hopefully I have enough other flower varieties to sweeten their honey all summer long.

So, the natural dyes I will be focusing on this summer are avocado pits, onion skins and possibly "black" hollyhocks.

Onion skins are perhaps the easiest, safest and most fun for beginners. Onion skins and black hollyhocks (which are deep, dark red when the sun comes through them) can be colorfast and lightfast, depending upon mordant, which is what you soak the yarn or fabric (or T-shirts) in prior to dyeing to set the color, and both can produce a wide variety of colors, depending upon fiber and mordant used.

I wasn't terribly happy with my last batch of hollyhock-dyed cotton fabric strips; they faded from gorgeous shades of plum to boring shades of tan without any daylight exposure, so I haven't used my hollyhocks for about three years now. Then I remembered I had tried using soy as my mordant on that particular dye batch, and perhaps that's why the color faded so fast. I will be using alum and cream of tartar this time around.

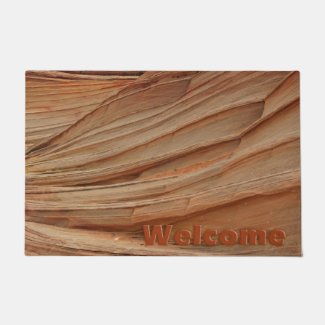

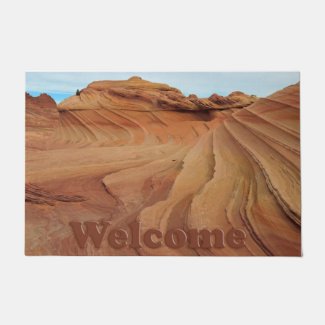

Avocado pits (and skins, although I haven't been saving mine) have built-in mordant, and the Wave-reminiscent orange/red/pink/brown hues will last and last. If you are familiar with my love of red rock, the range of color from avocado pits and skins will tell you why I love dyeing with them. Plus, we love eating avocado in many ways. Did you know it can replace eggs and/or butter in recipes?!?. Very healthy stuff.

Avocado-dyed colors can fade in continual direct sunlight, as any natural-dyed product will do. Heck, you shouldn't even leave store-bought clothes out on the clothesline for hours on end in direct sunlight because those will fade, too. You probably shouldn't wear anything natural-dyed in a swimming pool. Chlorine does nasty stuff to natural-dyed colors, including bleach them into non-existence. But why in the world would anyone want to wear a natural-dyed, hand-knit sweater into a swimming pool?!?

Another of my favorite natural dyes is indigo, which is what is used to color blue jeans. However, that is not a beginner process at all, and it's pretty darned stinky. I still want to know who peed on their mom's dye vat two or three thousand years ago, enabling the discovery of colorfast natural blue dye, which is rare. (Woad is the other reliable source of blue, and it's processed the same way.) And what did the mom do when she found out what her boys had done to her dye vat (before she discovered blue)?!? Due to the technical and advanced potentially dangerous (for unsupervised children) processing, I won't be including indigo (or woad) in this dye workshop.

Stove-top natural dyeing is not a fast process. Solar natural dyeing takes even longer. I can't solar dye from sometimes October often until May unless I'm using small containers I can leave in the window. If you plan to solar dye, you'll want to make sure you begin after the danger of overnight freeze has passed, and you'll want to finish up before the first overnight freeze of autumn (or winter, depending upon your climate).

Solar dyeing will take me all three months of summer (and a month of autumn if I can squeeze it in, depending upon weather). I'll be starting the first batch of avocado pits this weekend, and the dye extraction process will take all summer. The longer I let the pits soak in the sun, the deeper the dye color will be. (I once kept a canning jar of crushed avocado pits in the living room window for nearly 18 months, and oh, my goodness, you would not believe the gorgeous Moab hues I obtained from it!)

Onion skins can take a week to a month to create dye. Hollyhocks can go a month or two, depending upon when the first blooms begin appearing.

Natural dyeing works only on plant-based or protein (animal)-based fiber, which means cotton, silk, linen, wool, etc. You can't dye acrylic or polyester or other man-made fibers with natural dyes. I'll be using cotton yarn and cotton fabric. I have a bunch of wool ready to dye, but wool can felt if you change the temperature of the dye too quickly or shock the fiber by moving it from one temperature to another different temperature. You also can felt wool by agitating it too aggressively in the rinse cycle. You have to be gentle with wool. You have to treat it like a human baby. Don't make it uncomfortable. In my opinion, it's not a beginner fiber.

Once you decide what fiber and dye you'd like to use, you'll need to select a mordant (unless you are using avocado pits), which I do based on what color I would like to obtain.

For me, the best mordant is alum, which is cheaper at the pharmacy or online than when you buy it at the grocery store. Non-herbal tea also works well as a mordant. Both also are easy to dispose of when you are done. You can read more about other available mordants (as well as warnings about using them)

here, although I won't be using them in this workshop.

You'll also need a big pot and preferably a big wooden spoon that won't be used for food. Although onion skins do not present any risks, I still do not use any of my dye tools for food preparation. I bought the biggest stew pot I could find for the cheapest price at the closest department store. I think I paid $6 for the 16-quart cheap pot. I had purchased a whole set of wooden spoons; I just pulled one out and labeled it and the pot "DYE" with a permanent marker. I also bought the cheapest and biggest strainer I could find, which costed about $8, and attached a label to it, since it had no place to easily label with a permanent marker.

Lizard bought me a box of disposable latex gloves. That may have been the most expensive dye tool I own, probably around $18. But I've been using these gloves for about six or seven years now, and I still am not close to running out. I put baby powder inside them before wearing them the first time because that makes it easier to get my hands in and out of them. Each pair of gloves is used for a month or so before I dispose of them.

If you plan to solar dye, as I am, you also will need large glass or clear plastic jars big enough to hold your dye stuff but not so big that you can't lift it when full. These also will not be used for food preparation after you've used them for dyeing. I often use canning jars; I've purchased two sets specifically for dyeing. But I also will use empty spaghetti sauce jars, pickle jars and clear plastic ice cream/gelato containers. I've used foil instead of lids when I don't have lids, but be aware that aluminum foil can rust and can alter the color you are trying to achieve. Rust is a mordant. Some dyers use iron pots to mordant their yarn. But again, you won't be able to use the iron pot for food after using it for dyeing.

Solar dyeing requires periodic shaking/stirring and checking for mold. (Mold stinks and also can turn your dye gray or brown.) Back in my photography darkroom days, I learned to gently turn the tank upside down and back several times so as not to incorporate air bubbles, which leave circular marks on the negatives. I use the same method to "agitate" my dyes with lids, often every day, but at least every two days. I stir the foil-topped jars every day or two, checking for mold and rust, spooning out any mold into the unwanted weeds and replacing the foil as needed.

I also bought a very cheap blender to grind up my dye stuff... I think I paid less than $8 for it and have been using it for six or seven years now. It works great for avocado pits, as well as just about any other natural dye stuff. I run hot plain and soapy water through it after each session to clean it out, and the hot, soapy water gets dumped on the weed patch I'm not very successfully discouraging. But I do still keep trying.

The blender also doubles for making homemade paper with recycled paper and plant material, but that's a whole different process. But I'm letting you know, just in case you ever get interested in making your own paper. My little neighbor LOVES to help me make paper, and we'll probably do that again this summer, but I'm not planning to do a workshop via my blog until I become much more proficient and experienced.

The dyeing (and paper-making) rules (both natural and conventional) I've always heard and have always tried to follow religiously are:

1. Always wear gloves and a mask.

2. Never use dye utensils for food preparation. Always keep them separate.

3. Always work in a well-ventilated area, and don't work over or close to furniture or flooring that could be stained. Which also means wear clothing on which you don't mind catching spills. One of the Murphy's Law aspects of natural dyeing is that if you want the color to stay, it probably won't, and if you want it to wash out, it probably won't.

4. Always dispose of dye stuff and mordants in a safe way.

That said, I'm going to give you a couple of weeks to begin collecting onion skins, avocado pits (and/or skins - both are processed the same but make different shades of red/orange/pink/brown), and your tools. Onion skins may be dried and kept in any dry container until you are ready to use them. Clean avocado pits and skins of any avocado, and store in resealable bag in the freezer until you are ready to use them.

If you have kids, they will LOVE to see the magical change of color in red onion skin dyeing. We love red onions, and when I buy one at the store, I will always clean the display of remnant and stowaway skins. When the bag gets weighed, I'm paying for both the onions and the super-lightweight skins, and the store gets a free onion cleanup. I once had a cashier ask me what I was doing with all the red onion skins, and when I told him I do a lot of natural dyeing, he asked if I was going to dye my hair with the onion skins.

Um, no. But apparently that is a thing. Onion skins also can be used to color Easter eggs...

I'll see you again in two weeks to help you get your first jar of dye stuff simmering.

Have fun!

Linking up with

Busy Hands Quilts and

Confessions of a Fabric Addict.